The best recipe for getting through a Midwest winter is (for me) staying focused and busy. However, the best recipe for getting through February is to slow down and take a minute for myself. When I thought about what would make me happiest last week, finishing something sounded like the best gift I could possibly give myself. So I took a little time to complete another step in a (so far) six-year-long miniature painting project that I return to every now and then when I feel like I can steal some time for it.

Over the past ten years when I’ve stepped away from my main focus in order to paint, I’ve come away learning something important about my main discipline, or art in general.

The Tale of Four Finished Stories and 206 Ships

In November 2013, on the way home from my twenty-year high school reunion, we stopped at a Starbucks in Indiana, and while we were inside, a tornado demolished the Starbucks and tossed the cars in the parking lot. Before it hit, I stood at the counter with my drinks and saw the tornado approaching. We huddled in the brick restrooms as the tornado tore the building apart.

Most things seemed less important after that. It suddenly came clear to me that the only things that mattered were family, health, and dreams. All the rest of the things we worry about are inconsequential.

Panic

Some things seemed more important right after the tornado. What was I doing with my life? I worked a regular job and worked on creative projects in the margin. I defined myself primarily as a writer and game designer at the time. The draft of the “S” section of the Dungeons & Dragons 5e Monster Manual was on my computer in the little gray Corolla the tornado hit. But the freelancer model was changing, and I knew my five years writing D&D were coming to a close. I was ready to return to where I left off writing fiction prior to the start of my D&D work in early 2009. I felt an immediate, vital compulsion to make good use of my new lease on life.

In January 2014, I resolved to write four complete, edited short stories, one week after another, and have them ready for publication by the end of the month. Back then, I was writing two thousand words before 6 a.m. every morning, I was used to turning over polished prose to my freelance clients for five years, so I felt my chances were good.

Failure

At the end of the first week, the story I was writing had encountered a few snags. I needed to rewrite parts of it to make sense of the thing, but I hadn’t worked out the way forward. I decided to start on the second story and let my subconscious solve the problems of the first one; I’d come back to that once I figured it out.

By the end of week two, I’d written most of another story. Only… it wasn’t quite working, and there were some issues. I’d been so focused on making that one work that my subconscious hadn’t unraveled the troubles with the first story; all my focus was on story two. As time was ticking away, I knew I needed to get to work on my third story. I was beginning to think I might not make it to the fourth story, needing the final week in January to resolve the issues with the others.

By the end of week three, I was working on a (third) tangled mess of a story I couldn’t see may way through. In my wake were two other tangled stories without resolutions. It was late January, 2014. My new lease on life had amounted to nothing but failure. I recognized the kinds of stories I wanted to write, but I didn’t understand how to make them happen. I wasn’t going to understand that in the fourth week of January. I stood in the pit of despair. In the fourth week of January, 2014, I did the only thing I could do to get out of that pit: I quit.

Zen and the Art of Eclipse Ships

I felt miserable. My birthday came around in February, and Elizabeth took me to the local game store and told me to pick something. I chose Eclipse: New Dawn for the Galaxy, the physical version of a giant space empire game I had enjoyed on the iPad.

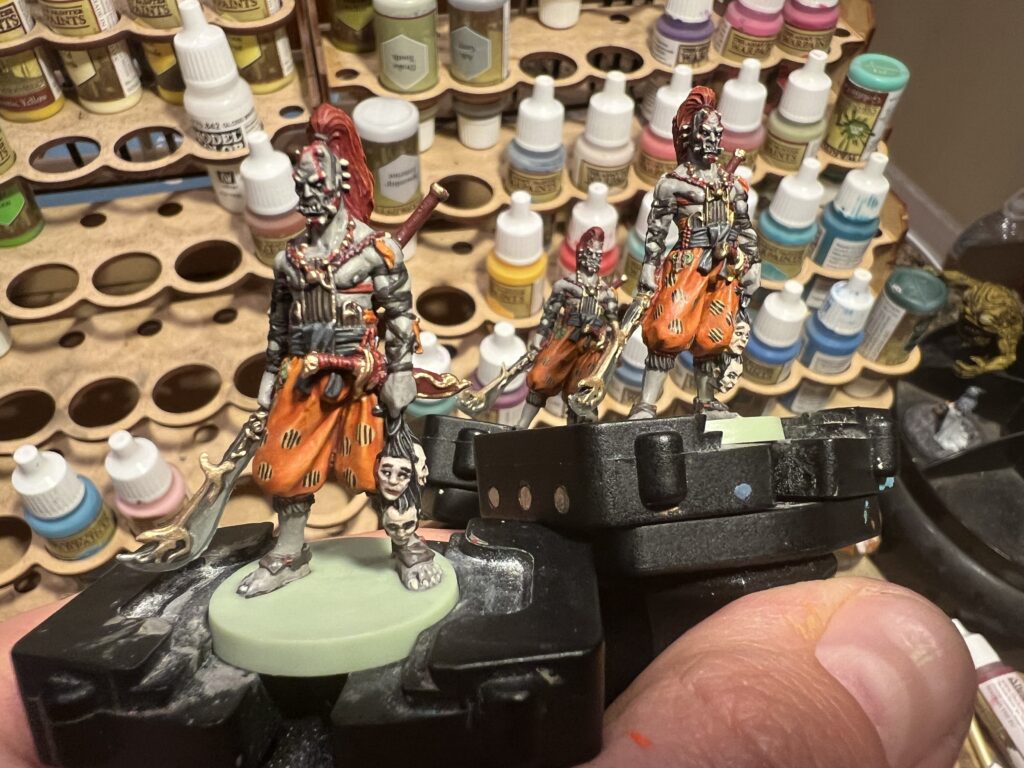

I was inspired to try my hand at painting the game’s 206 ships. In February and March, 2014, I went to the kitchen counter night after night and painted the ships from Eclipse.

Each faction in the game had their own contingent of (typically) eight interceptors, four cruisers, two dreadnoughts, and four star bases. Every time I finished one of these contingents, I felt this rush of satisfaction. Whenever I finished a whole faction, that rush doubled.

Sometimes I listened to books while I painted. Sometimes I listened to music for hours, or podcasts. Hours flew by as I focused on the tiny details. But despite only working on pieces for a hobby game, these hours felt so productive and peaceful.

The Struggles, the Lessons

As wonderful as the time painting Eclipse was, I still struggled I learned some lessons about art, life, and my own process.

1. The hardest part is figuring out what it’s going to be

Universally, this has proven true for me, from art to art. Before I started on the ships, I’d have to decide what color they were going to be, which parts needed to be painted, how I’d emphasize or highlight them, whether I’d try freehanding any designs. Sometimes I’d jump in too quickly because I wanted results immediately. I almost always regretted this. Knowing the overall direction is important to finding my way to the end of a piece of art, but puzzling out what that direction is can be both daunting and time consuming. Once you know your destination, though, you understand the basic shape of your journey.

2. I will screw it up every way there is before doing it right, and that’s ok

This has always been true. Even back to my theatre days when I would learn fight or dance choreography. I always began as the most uncoordinated and awkward, and the steps took me the longest to learn. Once I learned them, I fully committed. But first, I had to do it wrong—seemingly every way there is. If there is a way to do something poorly, I have to explore that space. I need to know what failure looks like before I can measure success.

3. It’s going to look really bad before it looks really good

The blank page, unpainted figure, empty rehearsal space, and set up photography studio hint at the promise of great work to be made. Begin writing, painting, rehearsing, or photographing, and what began clean starts to look messy, awkward, and amateurish. This long, awkward stage lasts most of the project, punctuated by occasional moments of inspiration. It’s important to remember that this is the way it happens every time, with every project. Keep working. Mysteriously one day the project doesn’t look quite as awful as it did the day before. And though each further step feels arduous and finicky, each one is a step forward toward making something beautiful. Somehow it transforms. I don’t know any shortcuts in the process that lead from promising to amazing in one step.

4. There is such a thing as good enough

Many times painting Eclipse, I’d focus on a minor detail—something I just had to include. The piece looked great already, but what if I fixed that tiny detail that no one would ever notice but me? Invariably, trying to perfect what already looked great resulted in something worse, not better. That’s when I’d make extra mistakes or spill black paint on yellow or something equally annoying that would take a lot of extra time to correct.

Once I started to learn this lesson, I’d leave the pieces, go to bed, get up the next day, and look them over. Most of the time, I couldn’t remember, or locate, where my problem area had been. I was looking so specifically at something so small and inconsequential that it didn’t matter. However, I needed the time and space to walk away and come back to it in order to truly see it again.

It was also important to remember this old adage: Art is never finished, only abandoned.

At first, it can be difficult to let go and accept that a work is good enough—that we’ve done our best and are at the point of diminishing returns. Nevertheless feelings of relief or pride that follow shortly after finishing such a task can be exhilarating.

5. Detach from identity and outcome

At the end of two months, I realized I had painted 206 ships.

I could not write four stories in one month. But I could paint 206 ships in two.

How does that work?

Back then, I had thought of myself as a writer, and my identity was wholly invested in being a writer. If I wrote and it was bad, then I too was a failure.

However, I did not, then or now, identify as a painter. I didn’t need to succeed as a painter or compete as one. I don’t care that there are better painters in the world. I could paint 206 ships because success or failure did not define my identity the way that writing did.

Over time, I learned to adopt this attitude toward writing and other arts. And I did eventually learn how to fix broken stories thanks to the mentorship of playwright Dana Lynn Formby. I remember one month feeling gloomy because I’d written a story per day and only had four good ones at the end of the month. As I groused about this to a writer friend, she said, “You wrote four good stories in a month.”

“But I wrote twenty-seven pieces of utter garbage!”

“But you wrote four good stories… in one month!“

The object was simply to do the work.

6. Keep showing up to do the work

That’s the other lesson.

Keep going. Keep getting up and doing the work, moving forward. Sometimes the process is slow, especially with the work that matters most to us.

For me, the lessons I learned from going outside the art I was invested in taught me how to do the art I was invested in. The lessons I learned from painting miniatures were the things I needed to practice in every other art form. I just couldn’t learn them in the art form I so closely identified with because I was too close and too invested.

As we learn new skills, they teach us more about the skills we know. Perhaps we can only master our skills by stepping away from them so that we can see them, and ourselves, as we are.

Follow Me